By Tony Attwood

It is easy to assume that because football began at Highbury in the late summer of 1913, that the ground was completed. But of course this was in the days before the notion of health and safety took hold, and we are reminded of the fact that the ground was far from complete as the press (I suspect following a tour organised by Henry Norris for their benefit) reported on 1 February 1914 that the walls of the main stand consisted of nothing other than tarpaulin.

It might also be easy to assume that Henry Norris devoted his time to Arsenal and the continuation of the building of the Gillespie Road ground, but again we can be reminded that this was not the case by the fact that on 3 February the London County Council considered a request made by the Allen and Norris partnership to delay the date by which streets on the Crabtree Lane Estate in Fulham had to be ready for use.

There was nothing particularly unusual in this. Completion dates were given for work to deter companies from buying up land ostensibly to build houses and then doing nothing with it. London already had a serious housing shortage, and the need for people to work in the city that was the heart of the Empire, was constantly growing. The system was thus not designed so much to hold developers to a strict timetable but rather to ensure that the work promised was done within a reasonable time.

Norris and Hall would have had no problem with this application since their reputation as house builders was secure and a new finish date of 17 October 1914 was agreed, although as it turns out, in June the pair were back before the Council with a similar request in relation to their work at Southfields, Wandsworth.

This might indicate that the two men did not have a big enough organisation to compete two major housing estates at once, but it might also be that the loans and guarantees that Norris had been forced to give to transform the Gillespie Road site into a football ground, and the bankrolling of the club that he had undertaken from 1910 onwards, had put a little strain on his fortune, and perhaps on the partnership’s ability to raise more funds.

Yet at the same time, the partnership was not ready to retrench, for on 6 February – the same week as they had been seeking an extension for their Fulham project the partners made the official announcement that they were in the process of becoming the owners of a five-acre plot of land in Fulham between the Crabtree Farm and the Pimlico Wheel Works. As Sally Davis points out this was “immediately north of the land they already owned and were building their Crabtree Farm Estate on.”

Davis also raises the point that the partnership might not actually have built on the plot, but in fact bought it to stop the development of an industrial site behind the houses they were still building in Fulham. It is also possible that they were considering the site for yet further housing, but knew their chances of completing the work while other projects were ongoing was slight, and so they left the land. They would however have had to give a date by which building would be completed – but the war put an end to the validity of all such promises.

As for Woolwich Arsenal FC their next game was away to Bury, on 7 February, and this ended as a 1-1 draw. The following Saturday Huddersfield Town were the visitors to the Gillespie Road ground, and another fine crowd – this time of 25,000 – turned up to see a home defeat, by 0-1.

A further week on and Arsenal were away, and suffered a second consecutive defeat, this time to Lincoln. The game was noticeable for being the second major defeat of the season with the score 2-5. It was the final league game for William Spittle, one of those players who filled in when the first choice player was not available – in his case either at inside left or inside right.

But Spittle also carried another unfortunate record for despite playing seven league games for the club, not once was he on the winning side. He was recorded as being on the books until 1919 but did not play for the club in the league after this game.

And this was not the only surprising defeat on this day, for the same saturday afternoon also saw the largest away win of the season with Fulham losing at home to Bradford PA 1-6. Norris as a director of both Fulham and Arsenal could not have been best pleased that evening although would have had to put a brave face on events.

What made Arsenal’s result all the more remarkable was that this was one of only two games that Lincoln won away from home all season, and the event included their scoring just under half of their entire away goals total for the whole season in one match! Fulham at least could be consoled over the Bradford game by the fact that they were beaten by a team that ended the season being promoted to the first division. Arsenal had no such consolation.

Arsenal did however have the subsequent lift by returning to winning ways for the last match of the month with a 2-1 win over Blackpool but it was their only win in the last four games, and it was clear that if they were to gain promotion, matters had to improve.

But despite this Arsenal’s position was still looking good, largely because several of their nearest rivals had either had bad results themselves or were still involved in the FA Cup and therefore not able to play as many League games as Arsenal

| Pos | Team | P | W | D | L | GF | GA | GAvg | GD | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Notts County | 30 | 18 | 6 | 6 | 62 | 27 | 2.296 | 35 | 42 |

| 2 | Woolwich Arsenal | 28 | 16 | 5 | 7 | 41 | 31 | 1.323 | 10 | 37 |

| 3 | Hull City | 27 | 14 | 7 | 6 | 46 | 23 | 2.000 | 23 | 35 |

| 4 | Leeds City | 26 | 15 | 3 | 8 | 60 | 34 | 1.765 | 26 | 33 |

| 5 | Bradford Park Avenue | 28 | 16 | 1 | 11 | 50 | 40 | 1.250 | 10 | 33 |

On 4 March 1914 London County Council finally granted planning permission for the Gillespie Road stadium, seven months after it opened and one year to the day after Norris announced that Gillespie Road was the site of the new ground. This might sound bizarre to us now, or indeed illegal, but in the early part of the 20th century, this was mostly how matters went.

Of course anyone developing a spot of ground for a new use while planning permission was still pending did risk having it refused, but planning controls were far less of an issue at this time than in the 21st century.

Besides, had the matter gone to planning prior to the building, there could have been – and indeed there were – many theoretical issues raised, just as there were when Arsenal applied for planning permission for what became the Emirates Stadium. Then we had the emotive talk of local residents being “prisoners in their own homes” on match days, but the Emirates, as with Highbury before, found that within ten minutes of the final whistle much of the crowd had dissipated. By the spring of 1914 the Highbury Defence Committee was but a rump, and its days of influence gone. Islington Council knew that they had no chance of overturning the building of the ground, and had likewise simply welcomed the additional payment of the rates (now known as council tax).

Furthermore by the time of the final hearing there were many local traders who positively loved the presence of Arsenal in the area. With no alcohol in the ground the pubs around the area did a roaring trade – the highly restrictive licensing hours of much of the 20th century did not come into effect until after the outbreak of war in 1914 – as did the restaurants and street vendors.

On 7 March Arsenal played an away goalless draw with Nottingham Forest in front of 10,000, but even before this match most Arsenal fans were focussed on the next match on 14 March: the first London derby at Highbury.

Arsenal had played their first London derby on November 9, 1907 with the result Chelsea 2 Arsenal 1 in front of 65,000 . The return match at Plumstead on March 7, 1908 was a goalless draw with 30,000, in the ground.

And 30,000 was the attendance again on 14 March 1914 as Arsenal won 2-0 – revenge for the humiliating defeat at Craven Cottage.

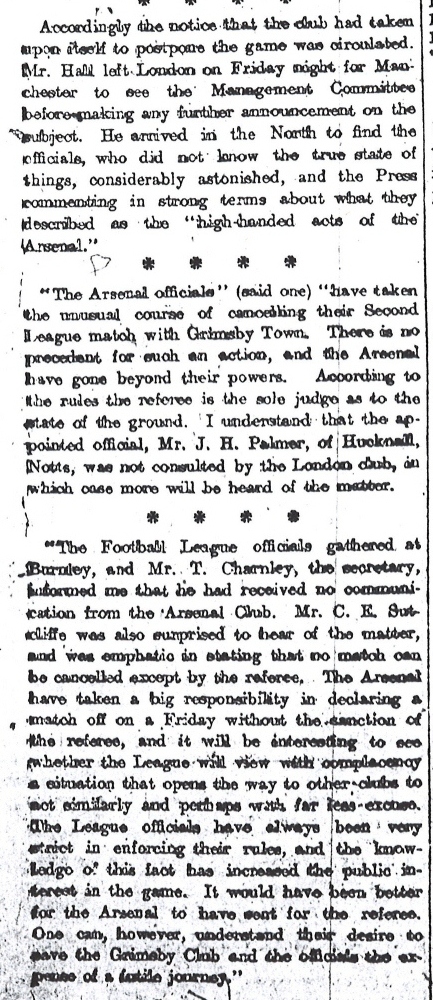

This was an encouraging upturn but then disaster struck as Andy Kelly has reported in an earlier article on this site. As he wrote…

On the evening of Thursday 19 March a torrential downpour hit north London. The sewers were unable to contain the rainwater which flooded down Highbury Hill pushing mud against the west terrace boundary wall. The wall was unable to take the pressure and started listing in towards the terracing.

The following morning the staff arrived at Highbury and noticed the problem with the wall. The directors were now faced with a dilemma. Arsenal were due to host Grimsby the next day.

A surveyor from the London County Council was called in and he told the directors that, although it was a danger to public safety, he would not condemn it or close the ground.

The directors discussed several options including not allowing spectators on to the west terrace and playing the game behind closed doors, but ultimately a decision was taken to close the ground until the wall was made safe. This was a risky option as it could result in a points penalty from the League: worrying given that Arsenal were still second in the table and heading for promotion. Thankfully, the Football League saw sense and did not censure the club for taking this action.

It is interesting that the club is called “The Arsenal” in the commentary, although it was still formally Woolwich Arsenal.

As for what was needed to be done to the wall, the worst case scenario would have been that the wall would have to be demolished and re-built. The damage wasn’t that bad and, incredibly, the solution was to employ 100 labourers to shovel the mud that had built up against the wall onto the terrace!

Meanwhile back with footballing matters, on 24 March John Butler joined Arsenal FC. His first game in first team not until 1919 although it would have been much earlier had it not been for the war. He continued with the club until April 1930.

Highbury finally reopened for business two weeks later for the reserve game against Fulham on 2 April. In total 3 games had to be postponed, including the reserve game against Portsmouth which had been designated as Charlie Lewis’ benefit game.

But before that, Arsenal had one more game to play – on 28 March. The result unfortunately was Birmingham 2 Arsenal 0. This was the start of four match run without a win which cost the club promotion in its first year back in the second division. This match was also almost certainly the source for the picture of the away kit that was falsely used to “prove” that Arsenal wore blackcurrant in the first season at Highbury.

Here is the end of month league table, extended down to 11th to show Fulham. Arsenal had slipped to third, but now had a game in hand, and had been aided by the wavering form of all those around them other than Notts County, who it seems could not be beaten. Herbert Chapman’s Leeds City was also creeping up into a challenging position.

| Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | F | A | GAvg | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Notts County | 34 | 21 | 6 | 7 | 73 | 34 | 2.147 | 48 |

| 2 | Bradford Park Avenue | 32 | 19 | 2 | 11 | 58 | 44 | 1.318 | 40 |

| 3 | Woolwich Arsenal | 31 | 17 | 6 | 8 | 43 | 33 | 1.303 | 40 |

| 4 | Leeds City | 31 | 17 | 4 | 10 | 69 | 41 | 1.683 | 38 |

| 5 | Hull City | 32 | 15 | 8 | 9 | 52 | 32 | 1.625 | 38 |

| 6 | Leyton Orient | 31 | 15 | 6 | 10 | 40 | 28 | 1.429 | 36 |

| 7 | Bristol City | 32 | 15 | 6 | 11 | 47 | 44 | 1.068 | 36 |

| 8 | Wolverhampton Wanderers | 32 | 16 | 4 | 12 | 44 | 46 | 0.957 | 36 |

| 9 | Barnsley | 31 | 14 | 7 | 10 | 42 | 39 | 1.077 | 35 |

| 10 | Bury | 32 | 13 | 8 | 11 | 35 | 34 | 1.029 | 34 |

| 11 | Fulham | 32 | 13 | 6 | 13 | 42 | 39 | 1.077 | 32 |

The Henry Norris Files

Section 1 – 1910.

- Part 1. How Arsenal fell from grace.

- Part 2: heading for liquidation and the first thought of moving elsewhere

- Part 3: March and April 1910 – the crisis deepens

- Part 4: the proposed mergers with Tottenham and Chelsea.

- Part 5: The collapse of Woolwich Arsenal: how the rescue took shape.

- Part 6: It’s agreed, Arsenal stay in Plumstead for one (no two) years

- Part 7: Completing the takeover and preparing for the new season

- Part 8: July to December 1910. Bad news all round.

Section 2 – 1911

Section 3 – 1912

- 11: 1912 and Arsenal plan to move away from Plumstead

- 12: How Henry Norris chose Highbury as Arsenal’s new ground

- 13: Amid protests from the locals Arsenal’s future is secured

- 14: Arsenal relegated amidst allegations of match fixing

Section 4 – 1913

- How Henry Norris secured Highbury for Arsenal in 1913.

- Norris at the Arsenal: 1913 and the opening weeks at Highbury

- When Highbury opened, and “Victoria Concordia Crescit” was introduced

- The players who launched Arsenal’s rebirth and Arsenal’s games in October 1913.

- The rebirth of Arsenal after the move to Highbury: November 1913.

- December 1913, the alleged redcurrent shirts, and Chapman comes to Highbury for the first time

Section 5 – 1914