By Tony Attwood

Although this is primarily a history of Arsenal, and its chairman Henry Norris, who by February 1917 had been promoted to the rank of Captain in the British army, I am including brief elements of the war, as this obviously dominated the news and affected everything that happened.

And it has always struck me that in doing this one should note what happened on 1 February 1917, as it was so influential in the history of the war. And to do this I must backtrack briefly.

In 1915, Germany had adopted a policy of submarine warfare that included torpedoing without warning all armed ships, but specifically not passenger ships. However on March 24, 1916 a German sub had attacked the (obviously) unarmed cross channel ferry The Sussex. Around 50 people died.

US President Woodrow Wilson warned Germany that if this happened again it would enter the war against Germany, and in response Germany on May 4, 1916, pledged specifically that passenger ships would not be targeted and that merchant ships would not be attacked until the presence of weaponry had been established and even then provision would be made for the safety of passengers and crew. This became known as the Sussex Pledge.

However, thinking it would win the war quickly if the Pledge was abandoned, the Pledge was unilaterally rescinded in January 1917, and as a result the USA declared war on Germany on 6 April 1917. Thus 1 February 1917 has a particular moment of importance in the war as it marked the start of the Atlantic U-boat campaign.

On 2 February in Britain, bread rationing was introduced – a most certain sign that things were indeed getting grimmer by the day.

And yet despite everything, the football continued, although the crowds got ever smaller. By the start of February Arsenal had won 5, drawn 2 and lost 1 of the last eight – a huge improvement as they had only won 6 out of the previous 23. There was some hope for the future.

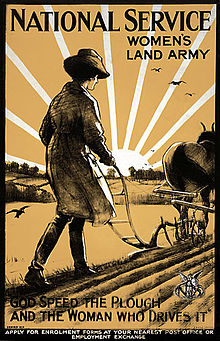

The upturn continued, at least in the sense that defeat was avoided, on 3 February as Arsenal drew away at Clapton Orient 2-2. However over this weekend the weather was particularly bad as the temperature dropped in London to -5ºC and it was perhaps therefore not too surprising that the crowd at the Orient was only 900. Meanwhile the formation of the Women’s Land Army was announced as an attempt to increase the production of food, replacing many farm labourers who had now been conscripted.

The Land Army was in fact part of a broader initiative in which the government sought to encourage men and women who were above the age of conscription, to volunteer to take over the jobs of young men who had been called up. And as you might expect public meetings took place to encourage this turn of events.

Also on this day “guidelines,” rather than strict rationing, were introduced for how much meat and sugar should be allocated to each person – it was up to shopkeepers whether they restricted their customers to these levels. The immediate tendency was to allow regular customers to buy what they normally bought, but not outsiders.

We still have no insight into Henry Norris’ work at this time beyond running Fulham council and being a member of the London County Council – his recruitment work had more or less stopped once conscription had started and the process of signing up all the men who were deemed eligible, while holding hearings regarding those who had reasons not to serve in the army.

However as we shall see at the end of the month, there was a feeling in the local council that the work load was now so great that nothing else could be taken on.

Meanwhile, as we have noted, Norris was obeying the government’s command to get people to invest in War Loan stocks. His approach had been for the council to buy £10,000 worth of the stock, and then to sell it on at par to anyone who wanted it.

What this in effect meant was that once again Henry Norris was helping the war effort out of his own resources – just as he did by paying for the maintenance of the two football battalions he had raised, before the army took them on.

This move led to an article in the Fulham Chronicle which reversed much of its previous approach to Norris, in which it had been critical of, among other things, the way decisions were being taken without debate, (the council as we have noted being made up entirely of Conservative members with no one representing any of the other parties). It started a campaign which sought public acknowledgement for the way in which Captain Norris was making his own contribution to the war effort.

It is interesting to note in passing that this approach of Norris – buying the stock and selling it on was very similar to his approach to Arsenal. He had taken over the shares in 1910 and then subsequently sought to sell them to the populace of Plumstead. Again after the building of the new stadium in Avenell Road and with the launch of the new Arsenal company following the move to north London he had taken on the costs, and then sought to reclaim his costs by selling on the shares.

Of course Norris was a wealthy man as a result of his work as a property developer, but it should be noticed, the risk in many of these ventures, was all his.

Arsenal’s next match was on 10 February, and resulted in a 3-2 home win over Fulham with a crowd of 4800 in the ground, and snow on the pitch. In the press stories were starting to circulate about a shortage of coal, caused of course by the fact that so many people involved in the coal industry (from miners to those who transported the coal from the pit head through the distribution chain to factories and people’s houses) were now with the army.

Sally Davis reports that at a meeting of Fulham Council on 14 February the council were now forced to meet in a small room in the upper part of the council’s building, as the main council chamber was being fully used to administer the War Loan stock – which continued to be on sale until 16 February. This fact suggests that once again Norris had risen to the challenge and used his rank, his presence and his political position to encourage people to buy.

Next up, on 17 February, Arsenal played Chelsea at Highbury, and it is a measure of how football fortunes had changed from this time one year before as Arsenal won 3-0 thus extending the good run. 7,500 turned up, which given the bad weather and the number of men now serving in the army, was a decent turnout.

At the match a collection was organised for Footballers’ Battalion, now as we have noted before, fighting in France.

Norseman in the Islington Gazette noted that Arsenal directors were rarely at matches these days (by which they probably meant Henry Norris) but did note that William Hall and George Davis were there, sitting alongside the FA Secretary Fred Wall. Also present was George Allison, whose role with the Arsenal we have noted as far back as 1910 when he started writing the club programme. But Henry Norris wasn’t there.

At the start of the war George Allison was the London representative of William Randolph Hearst’s newspaper enterprise and part of his job was to gather privately taken photographs of the war for use in the American press.

He then gained additional work attached to the War Office and the Admiralty procuring and commissioning pictures which as he says in his autobiography “would serve as pictorial propaganda” in North and South America, and Scandinavia. Indeed in his autobiography Allison makes it clear that he used the commercial backing of Hearst to get the best pictures, and then to provide them also to the government for propoganda.

Writing of the pictures he obtained of the German occupation of Louvain in Belgium, he states, “These inside shots of the enemy and their methods provided military experts with first hand data and my US organisation with a great beat over their rivals.”

Allison also relates in his memoirs how it was he who got pictures of the survivors of the Lusitania arriving in Ireland in 1915, which was, he suggests, of considerable propaganda help in moving the US into the war.

Back to 1917 however, and on 20 and 21 February Henry Norris was undertaking his regular work firstly with London County Council and the secondly with Fulham District Council, where there was another directive to encourage more young men who for whatever reason had not been called up via conscription, to volunteer. After that on 22nd Norris was involved as the local mayor in handing over an ambulance paid for by the Fulham Territorial Force to the London ambulance authorities.

There was also at this time much debate about the government’s request for all local land that could be found to be organised for food production. The Bishop of London had offered some of the land around Fulham Palace to the council, obviously expecting them to get on with organising the task of turning it into agricultural use, but the council turned down the offer and basically told the Bishop to see to it himself. They were, they said, too busy.

The local press didn’t think much of this response, and by the end of the week were letting the council in general and Norris in particular know exactly what they thought of the rejection of the offer.

The last Arsenal game of the month was on 24 February, a 2-0 away win over Southampton with 3,000 present. The result meant that out of the last 12 games Arsenal had won eight, drawn three and lost one. A tremendous improvement on the first part of the season.

The table below shows the results – the first column giving the match number. There were to be 40 games through the season all told.

| Match | Date | Opposition | Venue | Res | Score | Crowd | |

| 24 | 3/2/17 | Clapton Orient | A | D | 2-2 | 900 | |

| 25 | 10/2/17 | Fulham | H | W | 3-2 | 4,800 | |

| 26 | 17/2/17 | Chelsea | H | W | 3-0 | 7,500 | |

| 27 | 24/2/17 | Southampton | A | W | 2-0 | 3,000 |

The Henry Norris Files

Section 1 – 1910.

- Part 1. How Arsenal fell from grace.

- Part 2: heading for liquidation and the first thought of moving elsewhere

- Part 3: March and April 1910 – the crisis deepens

- Part 4: the proposed mergers with Tottenham and Chelsea.

- Part 5: The collapse of Woolwich Arsenal: how the rescue took shape.

- Part 6: It’s agreed, Arsenal stay in Plumstead for one (no two) years

- Part 7: Completing the takeover and preparing for the new season

- Part 8: July to December 1910. Bad news all round.

Section 2 – 1911

Section 3 – 1912

- 11: 1912 and Arsenal plan to move away from Plumstead

- 12: How Henry Norris chose Highbury as Arsenal’s new ground

- 13: Amid protests from the locals Arsenal’s future is secured

- 14: Arsenal relegated amidst allegations of match fixing

Section 4 – 1913

- How Henry Norris secured Highbury for Arsenal in 1913.

- Norris at the Arsenal: 1913 and the opening weeks at Highbury

- When Highbury opened, and “Victoria Concordia Crescit” was introduced

- The players who launched Arsenal’s rebirth and Arsenal’s games in October 1913.

- The rebirth of Arsenal after the move to Highbury: November 1913.

- December 1913, the alleged redcurrent shirts, and Chapman comes to Highbury for the first time

Section 5 – 1914

- Arsenal’s first ever FA Cup match at Highbury and a challenge for promotion: Jan 1914

- Arsenal February and March 1914; the wall falls down, the team slips up.

- The end of Woolwich Arsenal and of the first season at Highbury.

- Arsenal at the end of the world: May to August 1914.

- The newly named The Arsenal start their first season and go top of the League

- As the death toll mounts Arsenal keep playing: October 1914

- November 1914: The Times journalist goes to a reserve match without realising it.

- December 1914: The Footballers’ Battalion formed by Arsenal chairman and others

Section 6 – 1915

- January 1915: Arsenal players start to leave their club for their country

- Arsenal in February and March 1915: the abandonment of football is announced and the result is… curious

- April 1915: New revelations concerning perhaps the most important month in Arsenal’s history

- Norris promoted, the League loses interest but football pulls itself back together.

- Arsenal move into the London Combination in September 1915

- Arsenal in wartime: Norris’ genius for administration comes to the fore but reduces Arsenal’s playing staff.

- November / December 1915: the match fixing scandal comes to the fore: Norris is armed

Section 7: – 1916

- Arsenal in wartime: January 1916. The end of the first wartime league.

- Arsenal, February 1916: the 2nd league and a terrible tragedy on the pitch

- Arsenal: March – May 1916. The team in decline, entry to football taxed for the first time.

- Arsenal wartime league tables and player appearances: 1915/16

- Arsenal at war; Tottenham move out of WHL, Arsenal hit rock bottom. June to Sept 1916.

- Arsenal Oct 1916: a tragic death, a slow recovery

- Arsenal in wartime: November and December 1916

Section 8: 1917