By Tony Attwood

As I have reported through this series, as the debts of Arsenal were gradually paid off Sir Henry Norris had begun looking into the possibility of buying the land on which the Highbury ground was situated, and which was currently leased, and on 2 February 1925 Athletic News, undoubtedly after a conversation with Sir Henry, published a piece saying that the negotiations between St John’s College and Woolwich Arsenal Football and Athletic Company Ltd represented by Sir Henry had now been advanced to the stage Arsenal had in fact offered to buy not just the area that they now controlled but the rest of the college grounds as well.

It was a public sign that the entire project, started in 1910 and interrupted by war for four years had been an absolutely huge success. True, Arsenal were not champions or cup winners, but they had moved from being a club on the edge of extinction to a club whose crowds were the match of anyone else and whose future (if not always its present) looked exciting.

The reason for this has its history in the earlier report we made concerning the College grounds Arsenal occupied: the change in the law which meant that Church of England clergymen now had to have degrees while St Johns College focussed on preparing working men for a life of service to the church. The result was that their graduates were unlikely to be able to get a C of E job and thus the attraction of the College was severely diminished.

This change was now of course well established and St Johns found itself part of a world that was fast disappearing as the new was very much casting out the old. Double decker buses were appearing in London, the first TV transmitter was now working, and in work that was as little understood by the public at large then as it is now quantum theory was formulated for the first time.

In the context of the revelation about the attempts by Arsenal to buy the rest of the college grounds and the whole of the land it now occupied, it is not surprising to note the activity of the directors buying up any individual shares that came on the market. For although there would be significant debt from the latest transaction, unlike the leap into the dark when Arsenal obtained the full repairing lease in 1913, this would now be Arsenal’s land, to do with as it wished. As we now know, the club stayed at the ground until the land which became the Emirates Stadium was purchased in the 21st century. And by and large few would ever say that Highbury did not serve the club well.

But Arsenal on the pitch in 1925 were a sorry state. They had lost all three league matches in January and after two draws had lost their FA Cup 1st round game to West Ham. Worse, in league terms they had lost five of the last six and started February with yet another defeat – 0-1 away to Blackburn.

Indeed this defeat showed the rot really had set in because Blackburn were actually below Arsenal in the league at the time of this game, and this match had looked like a chance for Arsenal to break out of their run of bad form. Unfortunately injuries and whimsy were making Knighton revert to his old technique of moving players around, seemingly just to see what happened. Thus here Kennedy and Milne were missing, Rutherford was a long term injury and so Young who had started the season as a centre forward was now drafted in at right half and with no Dr Paterson available Hoar continued to deputise at outside right.

The defeat at Blackburn in terms of the league table were pretty awful…

| Pos | Club | P | W | D | L | F | A | G.Av | Pts |

| 1 | Huddersfield Town | 28 | 14 | 9 | 5 | 47 | 21 | 2.238 | 37 |

| 2 | Bolton Wanderers | 27 | 14 | 8 | 5 | 48 | 25 | 1.920 | 36 |

| 3 | West Bromwich Albion | 27 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 41 | 24 | 1.708 | 36 |

| 4 | Liverpool | 28 | 15 | 6 | 7 | 50 | 37 | 1.351 | 36 |

| 5 | Newcastle United | 29 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 45 | 26 | 1.731 | 35 |

| 6 | Birmingham City | 29 | 13 | 7 | 9 | 33 | 34 | 0.971 | 33 |

| 7 | Bury | 27 | 11 | 10 | 6 | 36 | 36 | 1.000 | 32 |

| 8 | Sunderland | 28 | 13 | 4 | 11 | 41 | 38 | 1.079 | 30 |

| 9 | Notts County | 27 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 24 | 19 | 1.263 | 28 |

| 10 | Manchester City | 28 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 55 | 47 | 1.170 | 28 |

| 11 | West Ham United | 27 | 11 | 6 | 10 | 37 | 35 | 1.057 | 28 |

| 12 | Tottenham Hotspur | 28 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 34 | 32 | 1.063 | 26 |

| 13 | Burnley | 27 | 9 | 8 | 10 | 35 | 37 | 0.946 | 26 |

| 14 | Aston Villa | 27 | 7 | 11 | 9 | 40 | 48 | 0.833 | 25 |

| 15 | Sheffield United | 28 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 31 | 40 | 0.775 | 25 |

| 16 | Arsenal | 27 | 10 | 4 | 13 | 32 | 32 | 1.000 | 24 |

Awful not just because Arsenal had sunk to 16th where they had once been challenging at the top, but also because the next match was against Huddersfield Town. And it was a rather particular game which has gone down in the history of football in England and one that will divert us for some while.

For now we come back to the issue of offside which has been mentioned before at the end of the report on January 1925. As I also reported earlier the key concern of the Football League – which in terms of games played was the dominant body in sport – was that crowds were going down, as we have seen.

We have noted how, at the end of January, a friendly game was played experimenting with the idea of changing the law on how many defenders had to be behind the ball when it was played forward.

Having suddenly leapt up to an all time peak of an average first division crowd of 24,036 in 1919/20 the crowds had been sinking year on year, and clearly 1924/25 was going to see a further major drop (once the season was over the figures came in at 21,036 for the average first division crowd – less than 1913/14). It wasn’t just a drop of 3000 per match, it was that the drop was carrying on year on year. A few more years, it was thought, and the decline would have taken the crowd level back to level of 1910/11.

Now we must remember that crowds were virtually the only source of income for the clubs, so this was a direct hit on their bottom line. And although salaries were controlled transfer fees were rising. It was a situation that had to be resolved.

The newspapers blamed the way the game was played, and in February 1925 the Times following the lead of other papers was bemoaning, “the general slowing up of the game through incessant, but necessary, whistle blowing, and the consequent exasperation both of players and spectators.”

Interestingly one of the games that was often cited as a prime example of the demise of the modern game was the fact that one of the FA Cup matches between Arsenal and WHU which had 30 offside calls. (There was no mention of drug taking or bizarre behaviour by the players!)

In fact what had changed was the growing use of tactics by managers; in a growing number of clubs players were being drilled more in the methodology of the offside law. So there were not significantly more teams playing an offside game but rather that those who did play it were better at it.

Those that did play the tactic tended to put their two full backs on the half way line while the team was attacking, with just one player lurking a little further back in case a ball was booted up field over the heads of the full backs. This meant that the attacking team could not venture into the opposition’s half until the ball was kicked upfield, and the one defender lurking there would have plenty of time to get across to the ball and clear it back upfield.

This ties in with our earlier observation that tactics were coming to the fore – something that Herbert Chapman was noted for (although he was not an exponent of the offside rule). What we did have was instead of everyone playing the same formation, variations were starting to emerge, and indeed although it is oft said that Chapman invented the WM formation with the centre half dropping back to play in between the full backs, this was certainly happening prior to this time with some teams. What Chapman did was modify WM to make it a much more effective approach.

In short the game had become more technical and the press blamed the decline in number of goals and as a result the size of the crowds on this. But there were other factors in the air at this time. The men who were now back with their families, or not working every hour of the day in munitions factories, were now fathers and after five and a half days at work, were opting to spend Saturday afternoon at home or in the park with the family, not at the football and in the pub.

But this seemingly was never understood by the football authorities for whom the whole concept of sociology was as alien then as the newly emergent quantum mechanics. The view was stated that crowds were down because of the offside rule and that was that.

At this point I must turn to Andy Kelly who earlier wrote an excellent article on the rule change for this site. Andy said,

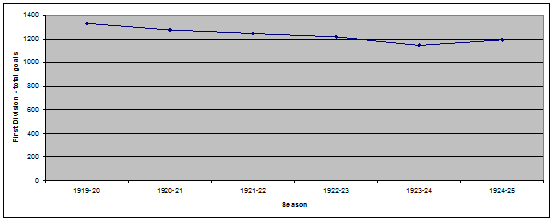

The first five seasons after the war saw the total number of goals in the first division fall by 14% – down to 2.47 goals per game. There was a slight recovery during 1924-25 but it was nowhere near enough to reverse the trend. The following graph shows the total goals scored in the first division for the first 6 seasons after the war.

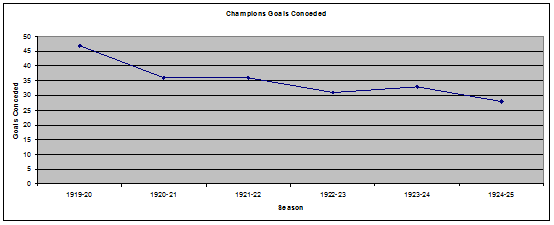

This was due to managers such as Herbert Chapman becoming more tactically aware. The following graph shows the goals conceded by the first division champions for the same period. Chapman’s Huddersfield were champions in 1923-24 and 1924-25.

The Scottish FA tried to change the offside law in 1923; but the International Board that was in charge of the laws of the game voted against this. (The International Board as we have noted before, comprised one representative from each of the English FA, the Scottish FA, the Welsh FA, the Irish FA and one member representing the rest of Fifa).

During the 1924-25 season the International Board decided to experiment with the offside law and chose Arsenal v Huddersfield Town on 14 February 1925 as one of two games for the experiment. For these two games, an attacking player would only need two opponents between himself and the goal to ensure he was onside.

Now it probably comes as no surprise to learn that Chapman took full advantage of the rule change as his Huddersfield side took a quick 3 goal lead and easily won the game 5-0. Knighton however didn’t seem to know what to do, and interestingly makes no mention of the honour Arsenal had at being selected as one of the trial teams for this match in his autobiography. As we have noted there is a lot of talk about drug taking, but nothing on the offside experiment.

The other experimental game on this day finished Bury 4 West Ham 2. For their defeat the Arsenal team was much as usual except that with Butler injured Blyth, who had played on both wings in matches in the early part of the season, got his second game at centre half. One can only wonder what was in the manager’s mind.

And indeed, one can’t help but wonder, knowing what happened in the summer of 1925, and knowing Sir Henry Norris’ connections with the FA and League through Lord Kinnaird and Arsenal’s representation within the FA and League, whether he suggested that Arsenal might be an ideal place for the trial match. He may even have already had his eye on Chapman as Arsenal’s next manager.

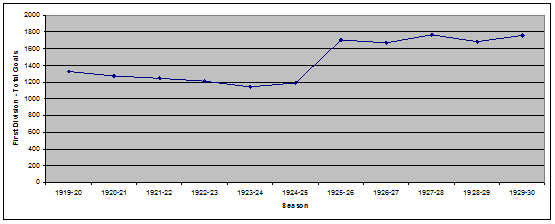

Andy continues: The experiment was deemed a success and during the summer of 1925 the laws were changed permanently. The results were immediate with a whopping 43% increase in goals in the first division to 3.69 goals per game.

The following graphs show the effect of the law change for the next 5 seasons.

In June 1925, at a meeting in Paris, football’s international governing body voted through a change in the off side rule.

Julian Carosi in commenting on the affair then noted an article in the Times of 25 October 1926 – that is just over a year after the introduction of the new off side rule that…

It was hoped that the alteration of the off side law would make for improvement, but unhappily expectations have not been realised. As a matter of fact the change has brought about an even greater looseness in the constructive art of the game. It is said, and probably truly, that the new off side law does not demand any change of methods, that all the fresh formations which were tried last season were unnecessary. But today every team is far more apprehensive in the matter of defence than used to be the case when an opponent was only legitimately placed if there were three men in front of him when the ball was last kicked. The result has been a tendency to concentrate on defence by half backs and this has meant a weakening in attack. At the present time it is not unusual to see a gap of twenty or more yards between half backs and forwards and, in such conditions, there must inevitably be a lack of combination between the two sections of the team.

This is not wholly accurate because Chapman most certainly was experimenting at Arsenal – but maybe he was alone in this matter.

What we can do however is gather some evidence and see exactly what happened as a result of this rule change. This diversion does take us away from our chronology and Arsenal in 1925, but I feel it makes more sense to complete the point here, rather than leave until subsequent seasons.

A number of reports in 1925 suggested that some clubs had worked out the tactic of catching the opposition off side with a great deal of success, and Newcastle was often cited in the media as the past masters of this technique of moving the defence up to the half way line as the opposition started an attack, as noted above.

One way to check this is to look at Newcastle’s total number of goals conceded across the years starting in 1905/6 when the league was increased to 20 clubs and compare the Newcastle figures with a few other clubs. I have chosen the clubs that came 3rd from the top and 3rd from the bottom of the first division, for clubs that come top or bottom often do so having outstandingly good or bad seasons, and are thus not representative of the league as a whole.

In the table below the first number in columns 2, 3 and 4 is the number of goals conceded. So if we look at 1905/6 Newcastle who came 4th conceded 48 goals while the 3rd from bottom team conceded 71 goals.

However one more figure is needed for the number of games per season increased from 38 to 42 after the first world war. Thus the number in [square brackets] in the 2nd, 3rd and 4th columns is the expected equivalent if 42 games had been played – this only applies up to the war as from 1919 onward 42 games were played each season.

Thus if we look down each column we would expected to see a fairly standard number of goals conceded for each team except with a sudden leap after the rule change. I have moved forward to focus on 1926/7 rather than 1925/6 since it could be possible to argue that the first year after the change was a special case with clubs getting used to the new change.

| Season | Newcastle goals against | 3rd club goals against | 3rd from bottom goals against | Average Division 1 crowd |

| 1905/6* | 48 (4th) [53] | 52 [57] | 71 [78] | 13,420 |

| 1910/11* | 43 (8th) [47] | 48 [53] | 71 [78] | 16,154 |

| 1913/14* | 48 (11th) [53] | 60 [66] | 70 [77] | 21,979 |

| 1919/20 | 39 (8th) | 51 | 77 | 24,036 |

| 1922/23 | 37 (4th) | 32 | 70 | 23,213 |

| 1924/25 | 42 (6th) | 34 | 58 | 21,609 |

| 1926/27 | 58 (1st) | 70 | 90 | 22,881 |

| 1929/30 | 72 (10th) | 81 | 80 | 22,647 |

| 1932/33 | 63 (5th) | 68 | 96 | 20,175 |

Summary of key indicators:

- * indicates 38 games, thereafter 42.

- Number in (curved brackets) is the position of the club.

- Number in [square brackets] is the expected equivalent if 42 games had been played – this only applies up to the war as from 1919 onward 42 games were played each season.

Thus we have three seasons before the war, three seasons post war before the change and three seasons after the change. Now if we look at the number of goals conceded these certainly went up for Newcastle – the club famed as the exponents of the offside rule after the rule change

If we look at goals conceded by the third club in the league, these had been going down and down until the rule change when they shot up dramatically. If we look at the third from bottom club their goals conceded rose dramatically after the rule change.

In short for all three categories of club (Newcastle, the masters of the old off side game, the 3rd club in the league, the club 3rd from the foot of the league), the number of goals conceded shot up after the rule change. So all that looks like a grand success for the scheme.

But… for there is always a but… although there was a rise in the average crowd at first, by 1932/3 that had vanished and at no time did attendances get back to anything near the level achieved in 1920/21. It turns out it wasn’t the decline in the number of goals that was the factor affecting attendances – although that may have been a contributory factor. It was something quite different.

I don’t have enough data to say what it was that took men away from football, and indeed I doubt that anyone does, but I might hazard a guess at the poor facilities, rising entry prices, the demands of family life and the economic circumstances of the country. Also one might note the escalating cost of transfers which fuelled the clubs’ needs to push for higher and higher entrance fees.

I personally doubt that the subsequent move to introduce the centre half as a central full back made for more negative football. Clubs were experimenting with the third full back for several years before 1925, and the notion that Chapman was the first to introduce the plan at Arsenal with WM is not supported by the facts.

But yes, the number of goals scored in the League went up as this table for all four divisions of the league shows

- 1919/20: 1332 goals (three divisions only)

- 1923/4: 1143 goals

- 1924/5: 1192 goals

- 1925/6: 1703 goals

- 1926/7: 1666 goals

- 1938/9: 1418 goals

What clearly happened was that after seeing how things worked in 1924/5 managers began to get the hang of the new law, although we must also note that by the time of the second world war there were still 746 more goals in the season than in the final year before the change. But then that was only 1.6 goals a game.