By Tony Attwood

All through the tumultuous period that we’ve been looking at in the previous articles, the fund-raising committee that had been set up before the full extent of this financial crisis was appreciated, had continued its activities. However on 6 June at a meeting in Rotherhithe, the committee resolved not to hand over any of the money it had raised to Henry Norris and William Hall, pending further developments, but instead they applied for shares in the new limited company set up to rescue Arsenal.

This was a canny move in that the money so invested would be safe, for if the new company failed to get off the ground, the money would be returned to the committee. They were thus using their funds to help get the new company operational, without putting the money at risk – at least not unless the company started, but then folded.

But meanwhile the number of employees at the Royal Arsenal factories continued to decline, in particular as the closure of the torpedo factory began, as it was moved to new premises in Greenock. This hit Arsenal FC particularly hard since the “torpedo boys” were avid supporters of the club, and had been at the forefront of establishing noisy, excitable and sometimes (as in the case of a visit to Nottingham Forest where the stand was set on fire) downright dangerous away support. It was also a rather strange decision by the government, for which there was no immediate explanation made available.

But from a footballing point of view, what makes the issue of crowd numbers so interesting is not just the huge decline in Woolwich Arsenal attendances since the promotion year, as we have noted, but also the fact that Fulham FC were also suffering. Figures released in the summer by Fulham as part of their Annual Report showed a loss for the year of £722, with the directors making negative noises about the lack of support for the local club. It really does make us wonder quite why Norris saw Woolwich Arsenal as an interesting investment, (although of course he was right to see it as such, in the end).

However in the round of club financial results that were issued at this time, Chelsea, the club with by far the biggest stadium in the country, announced by way of contrast with Arsenal and Fulham, a profit of £1945 for the year. And if we look again at the top 20 supported clubs in the league we can see exactly why…

| No. | Club | Div | Average | Change |

| 1 | Chelsea | 1 | 28.545 | -2,0% |

| 2 | Tottenham Hotspur | 1 | 27.560 | 36,1% |

| 3 | Newcastle United | 1 | 24.825 | -15,3% |

| 4 | Liverpool | 1 | 21.620 | 22,4% |

| 5 | Aston Villa | 1 | 21.125 | 11,5% |

| 6 | Bradford City | 1 | 20.640 | -5,6% |

| 7 | Everton | 1 | 19.110 | -17,0% |

| 8 | Manchester United | 1 | 18.740 | 3,3% |

| 9 | Manchester City | 2 | 18.540 | -5,7% |

| 10 | Fulham | 2 | 14.300 | -12,5% |

| 11 | Sheffield United | 1 | 13.840 | 9,6% |

| 12 | Blackburn Rovers | 1 | 13.805 | -6,4% |

| 13 | Bolton Wanderers | 1 | 12.445 | -3,2% |

| 14 | Oldham Athletic | 2 | 11.780 | -4,2% |

| 15 | Sunderland | 1 | 11.615 | -23,8% |

| 16 | Middlesbrough | 1 | 11.230 | -20,1% |

| 17 | Bristol City | 1 | 10.990 | -8,5% |

| 18 | West Bromwich Albion | 2 | 10.975 | -29,3% |

| 19 | Sheffield Wednesday | 1 | 10.720 | -16,5% |

| 20 | Arsenal | 1 | 10.395 | -20,2% |

But let us not forget the league table…

| Pos | Team | Pld | W | D | L | GF | GA | GAvg | Pts |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Aston Villa | 38 | 23 | 7 | 8 | 84 | 42 | 2.000 | 53 |

| 2 | Liverpool | 38 | 21 | 6 | 11 | 78 | 57 | 1.368 | 48 |

| 3 | Blackburn Rovers | 38 | 18 | 9 | 11 | 73 | 55 | 1.327 | 45 |

| 4 | Newcastle United | 38 | 19 | 7 | 12 | 70 | 56 | 1.250 | 45 |

| 5 | Manchester United | 38 | 19 | 7 | 12 | 69 | 61 | 1.131 | 45 |

| 6 | Sheffield United | 38 | 16 | 10 | 12 | 62 | 41 | 1.512 | 42 |

| 7 | Bradford City | 38 | 17 | 8 | 13 | 64 | 47 | 1.362 | 42 |

| 8 | Sunderland | 38 | 18 | 5 | 15 | 66 | 51 | 1.294 | 41 |

| 9 | Notts County | 38 | 15 | 10 | 13 | 67 | 59 | 1.136 | 40 |

| 10 | Everton | 38 | 16 | 8 | 14 | 51 | 56 | 0.911 | 40 |

| 11 | Sheffield Wednesday | 38 | 15 | 9 | 14 | 60 | 63 | 0.952 | 39 |

| 12 | Preston North End | 38 | 15 | 5 | 18 | 52 | 58 | 0.897 | 35 |

| 13 | Bury | 38 | 12 | 9 | 17 | 62 | 66 | 0.939 | 33 |

| 14 | Nottingham Forest | 38 | 11 | 11 | 16 | 54 | 72 | 0.750 | 33 |

| 15 | Tottenham Hotspur | 38 | 11 | 10 | 17 | 53 | 69 | 0.768 | 32 |

| 16 | Bristol City | 38 | 12 | 8 | 18 | 45 | 60 | 0.750 | 32 |

| 17 | Middlesbrough | 38 | 11 | 9 | 18 | 56 | 73 | 0.767 | 31 |

| 18 | Woolwich Arsenal | 38 | 11 | 9 | 18 | 37 | 67 | 0.552 | 31 |

| 19 | Chelsea | 38 | 11 | 7 | 20 | 47 | 70 | 0.671 | 29 |

| 20 | Bolton Wanderers | 38 | 9 | 6 | 23 | 44 | 71 | 0.620 | 24 |

The extraordinary point is that Chelsea were the top supported club in a season in which they were relegated.

Their ground, Stamford Bridge, was built as a football ground in 1905 and was initially offered to Fulham, who turned the opportunity down. But what particularly helped Chelsea was not a regularly large number of supporters in the ground, but the fact that for their very big games (most particularly against Tottenham and Arsenal, there was in reality no limit to the number that could attend. A couple of 60,000 attendances in the season worked wonders for their average.

Chelsea also incidentally caused the introduction of the “transfer deadline” at this time, as their attempts to avoid relegation included buying every player imaginable during the last few weeks of the season. It didn’t work but the League didn’t like the approach and introduced the deadline to start in the next season.

But back with attendances that table showing crowd averages sums up the whole problem for Arsenal. Add the decline in the number of employees in the local factories noted above, with presaged badly for the future, and the scale of the problem is revealed, along with the reality that money does not always equal success.

By late June Arsenal clearly needed to be getting ready for the new season, but this activity was being held up by the amount of time it was taking to resolve issues surrounding the original limited company’s debts. Worse, leaving aside the torpedo factory decision, on 15 June 1910 Woolwich Arsenal factories had started to lay off men due to a long-term downturn in armaments work following the end of the Boer War.

On 27 June Athletic News carried an article saying Woolwich Arsenal did not yet have a full squad of players, and although this was not a total disaster (since pre-season training did not start until August) it meant that many of the most promising young players who might be available were being signed elsewhere.

On the other hand the new transfer regulation only prohibited transfers in the last few weeks of the season, and so the commonplace habit of the time of managers seeing how their team performed in the opening games before making signings would carry on.

But there there was some pre-season activity, as for example on 9 July 1910 William Rippon joined Arsenal. He had already played for Hackenthorpe, Rawmarsh Albion, Sandhill Rovers, Kilnhurst Town, and Bristol City.

At the same time Hall and Norris, having sensibly confirmed the manager, now (presumably in consultation with George Morrell), hired a new trainer (the last trainer having been let go at the end of the previous season, because of the uncertainty surrounding the club’s future).

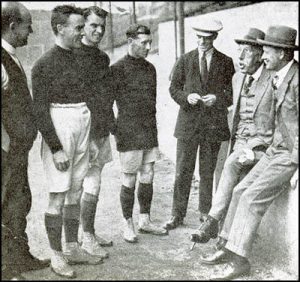

This signing happened in the week following the signing of Rippon, as the club appointed George Hardy, who had been working at Newcastle United. He stayed with Arsenal until 1927.

From left to right George Hardy, Bob John, Tom Whittaker, Joe Toner, Joe Irvine, Henry Norris, Leslie Knighton (Arsenal’s manager after the first world war – thus dating this picture to somewhere around 1924).

Hardy is one of the men from the era who went on to play a significant part in Arsenal’s history across the years.

For example in the first game at Highbury (September 6, 1913), George Jobey, Arsenal’s new centre forward, scored but then injured an ankle. As this tale is told Jobey was carried off by George Hardy. The story is that George Hardy borrowed a cart from the local milkman to take him to his home for treatment. Another version has him putting Hardy in a wheelbarrow.

Hardy stayed on at Arsenal when Chapman became manager in 1925, and on 2nd February 1927, Arsenal played in an FA Cup 4th round replay against Port Vale having drawn 2-2 four days earlier. According to Tom Whittaker (and remember Whittaker was hardly an unbiased observer in all that followed), “Arsenal were pressing hard, but things were not going just right and old George Hardy’s eyes spotted something he felt could be corrected to help the attack. During the next lull in the game he hopped to the touchline, and cupping his hands, yelled out that one of the forwards was to play a little farther upfield.” Chapman was furious and sent Hardy to the dressing-room.

Now, to return to the summer of 1910, early July saw the new limited company take over the debts and assets of the old Woolwich Arsenal and on 13 July, Woolwich Arsenal Football and Athletic Company Limited (the company which still exists as the ultimate company that owns the club) issued a financial statement showing it was already £700 in debt, through paying the players’ close season wages.

23 July was Henry Norris birthday; he was 45 but he was probably too busy to celebrate much. On 25 July Woolwich Arsenal was formally taken over by Henry Norris and William Hall in a meeting at the Mortar Hotel, Woolwich. It was chaired by George Leavey, who was confirmed as chairman of the new limited company with Henry Norris as a director at this stage. The solicitor Arthur Gilbert, was installed as company secretary.

The meeting approved the agreement between the new limited company and the liquidator, which transferred the assets of the original company to the new one, for £3050 and 200 shares

I will return to the details of the meeting in a moment, but first I want to deal with the financial situation.

Of course the new company now inherited the old company’s liabilities which included a debt to George Leavey of £1800, and a debt to Archibald Gray of £232. Archie Gray had been a stalwart of the Arsenal team since the moment they were promoted to the first division. However injury had deprived him of a lot of the 1909/10 season and he had only managed 13 matches.

There is nothing in the accounts to show why the money was owed to him. He had already played over 150 games for the club, and returned in 1910/11 for another 26 games.

But while this debt was included there was still nothing in the accounts relating to the debt to Leitch. This adds to my belief that the personal relationship between Norris and Leitch which had evolved across the years meant that they had come to their own agreement relating to the work Leitch would be doing in years to come.

Most significantly, Leitch was involved in the architecture of the new Fulham stand in 1905, the development that resulted in a notable (if financially not enormously significant) court case.

This came about because Fulham saw their existing stand as a “temporary structure”, which meant Fulham Borough Council had the right to give permission for its removal and replacement. The London County Council however saw the existing stand as a “permanent building” and thus under their jurisdiction. They also considered the current building to be dangerous and wanted it pulled down.

In the end the issue of whether the stand was a structure or a building went to court and it became clear in the case that Leitch had spent considerable time trying to get the LCC to define a “building”, only to find that they would or could not, something which counted against them in the hearings.

In the case that followed Leitch found an opportunity to show off his ability as a speaker in public situations, and he several times had the court in laughter with his wit. It was a great moment for him, as the case did much to enhance his public profile as journalists (never the fastest on the uptake) realised that here we had an engineer who didn’t specialise in bridges, railways, roads or viaducts as they were used to, but rather a man who built grandstands. They were fascinated, and Leitch’s reputation in London was secured. The Ibrox disaster was put behind him.

Henry Norris, one of Leitch’s two employers at the time (the other was Chelsea FC!) benefited from Leitch’s ability to entertain and be very specific in the court and as a result although Fulham were fined for a technical breach of the rules, the fine was trivial (4 shillings, or 20p in modern money). The LCC were left with £100 costs.

Norris knew how much Leitch had helped him, and a real bond between the two appeared to arise after this case, which could well help explain what happened to the debt Arsenal owed to Leitch after his work on the Manor Ground. It doesn’t explain how Leavey came to persuade Leitch not to press for payment of his bill when the work was first done – although as this was so soon after the Ibrox disaster it might well be a case that the promise of more work from the Arsenal board of the day, was enough to hold Leitch at bay.

Indeed it is possible that Leitch got both the Chelsea and Fulham jobs in 1905 on the back of his work at the Manor Ground.

Thus I suspect that in 1910 Norris promised Leitch that he, Norris, would eventually move Arsenal one way or another, and that Leitch would be the architect of a new super-stadium in London.

Now to return to the financial statement of the new company, this showed 1282 shares had been allotted to shareholders of which 788 £1 shares (just over 61%) had been fully paid up.

To help matters along William Hall and Henry Norris had also given the new limited company a loan of £369/19/4 (fractionally under £370) which was presumably to allow staff to be paid and for training for the new season to get under way. There is no reference in documentation of this loan being secured, so the chances of Hall and Norris getting anything back if Woolwich Arsenal failed was nil. But since Hall and Norris now effectively controlled the club, and since the deal with Leavey was that the club would only stay in Woolwich for two years (unless others came along to take up shares), it meant that in two years time Hall and Norris would have a free hand.

As for the meeting which we left a little earlier…

Sally Davis quotes the Kentish Independent as calling the meeting that disclosed these figures “turbulent”, while the West London and Fulham Times said there was “Considerable animation.” And yet accounts suggest only around 20 people came to the meeting, although among them was Dr John Clarke, who been centrally involved in forming the second Arsenal company (the first attempt to reform after the club itself teetered on the brink, before Norris and Hall took over). Dr Clarke has shown himself a man willing to work hard for his cause, as there are reports of him working his way from pub to pub in Plumstead and Woolwich looking for buyers of the new shares – haunts that he would not normally have frequented.

So it was natural that he would ask about why this latest Arsenal company was not including more locals in buying shares – most notably the people who had put their names down to buy from him, during his tour of the pubs.

Of course from this point it is was but one step to suggest that the Fulham men had been instrumental in bringing about Woolwich Arsenal’s demise. Leavey then had to defend Hall and Norris saying that they had had no part in Dr Clarke’s company (if we may call it that) stressing that it was indeed Dr Clarke and other locals who had worked on that project, and had been thwarted by the lack of local interest in buying the shares that were offered.

Henry Norris was of course asked if he intended to move Woolwich Arsenal out of Plumstead, and he said no, if there was support it would stay. And it was a reasonable response. Midway through the decade with Arsenal approaching promotion from the second division had found the locals had truly supported their team. But now with the club struggling they were not interested. If the report returned, (as the Chelsea fans had supported their club even when the club was going down), Arsenal would be fine.

Norris didn’t say it quite like that, but quite probably he didn’t need to, because everyone knew there was the other issue. The jobs in Woolwich were vanishing fast – and that was a matter of government policy which no one locally could affect.

The local press reports sided with the locals of course – after all it was the local people who bought the papers, and supporting Henry Norris et al, would have done their readership levels a lot of harm.

But meanwhile, somewhere along the line, one of the most prestigious men ever involved in Arsenal’s early history – Jack Humble – had bought shares in the new company. A very occasional player for Arsenal in its earliest days, he was the man who proposed paying players in 1891. He also carefully steered the club through thick and thin particularly during the crisis of 1892 when the club nearly came to an end, and as a result he was thus held in such high esteem that he had become the very first chairman of Woolwich Arsenal FC in June 1893.

Of late he had withdrawn from the club having felt he had played his part, leaving the board in 1907, with the club recognising the enormous debt that it owed to the man. But in 1910 he came back into the club, at the request of Henry Norris. It was a highly significant move.

The series continues…

Details of all the series of articles produced by the Arsenal History Society are to be found on this site’s home page.

We are currently evolving a complete series on Henry Norris at the Arsenal. The full index to the articles that cover the period from 1910 to this point are given in Henry Norris at the Arsenal

Perhaps the most popular element in the Norris story is that of Arsenal’s promotion to the first division in 1919. Therefore we have separated that story out below. It raises in part the question of the validity of the chief critic of Henry Norris: the Arsenal manager from 1919 to 1925 who Norris sacked. Thus in the selection below we include articles which consider the question as to the validity of Knighton’s testimony.

For the complete index on Norris at the Arsenal please see the link above.

The preliminaries

- April 1915: New revelations concerning perhaps the most important month in Arsenal’s history

- November / December 1915: the match fixing scandal comes to the fore: Norris is armed

The voting and the comments before and after the election

- The first suggestion that Arsenal could be elected to the 1st division.

- Arsenal in January 1919: rioting in the streets and the question of promotion

- What the media said about the election of Arsenal to the 1st division in 1919

- Arsenal prepare for the vote on who should be promoted to the First Division

- March 1919: The vote to extend the league and what the media said

- Why did the clubs vote for Arsenal rather than Tottenham in March 1919?

The Second Libel

The Third Allegation

The Fourth Allegation

Did Henry Norris really beg Leslie Knighton to stay and offer him the hugest bonus ever? And if so, why were there no new players?

- May/June 1921: Knighton the fantasist. The fourth allegation.

- Why did Arsenal manager Knighton turn down Man City but not buy players? Summer of 1921.

The Fifth Story:

The Sixth Allegation

- March 1922: Desperate times for Arsenal, Norris returns and the transfer limit allegation overturned

The Seventh Allegation

- Arsenal in the Summer 1923: another Knighton allegation but the evidence is again against him.

- Anticipation a plenty but another terrible start to the season: August 1923 – the non-signing of Moffatt.

The Eighth Strange Story